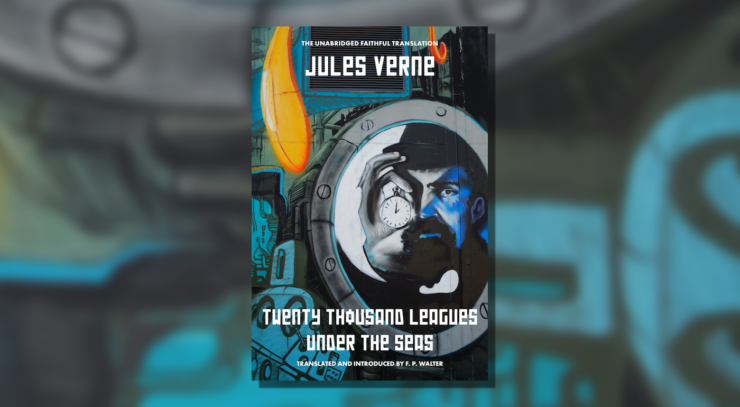

The original title of Jules Verne’s classic novel is Vingt mille lieues sous le mers, according to the editor of Warbler Press’ 2021 edition of the classic novel. It’s based on Frederick Paul Walter’s translation, originally published by the Naval Institute Press in 1993, and copyrighted 1999. All of which is to say that Walter’s translation is excellent, highly readable, and—very much to the point—unabridged. This is as close to Verne’s original as we’re likely to come in English, and it corrects a persistent error in the title. It’s Seas, plural, rather than the singular Sea.

This level of precision is characteristic of Verne himself. He’s writing in the 1860s, building entire worlds, extrapolating from bleeding-edge technology ca. 1867 (coal, steam, generating and storing oxygen, designing diving equipment based on materials available at the time). His viewpoint character is Professor Aronnax, a French naturalist who has been exploring the wilds of Nebraska in the Americas, and who has written two seminal texts on the flora and fauna of the seas.

Specialization in the sciences is clearly in its infancy. A man can turn his scientific attention in any direction that he chooses. He’s not bound to anything but his own inclinations and whatever income he can generate—whether it’s independent wealth, sales of his books, or stripping shipwrecks of their treasure.

It is a man’s world. The only female human in the book is a drowned corpse. Aronnax, like his hero/villain Captain Nemo, floats serenely above the merely mundane. The needs of daily life—food, clothing, hygiene—are fulfilled by mostly invisible hands. We’re told in detail what the food and clothing consist of and how they’re made, but we know little to nothing of any individual who makes them.

There is one named servant, Conseil, who is a sort of proto-Commander Data. He exists solely to say “Yes, Master” and “I do whatever Master wants.” He has no apparent ability to process the data he accumulates. Aronnax will turn him on and off by putting him in front of an animal or plant and triggering his compulsion to classify it.

Conseil’s opposite number is a Canadian harpooner named Ned Land (the surname is Significant, I’m sure). Ned lives to hunt and kill things. The long imprisonment on Nemo’s Nautilus does serious damage to his mental health. He has little interest in science, except insofar as he can kill whatever he finds and/or eat it; he spends most of his time plotting escape.

That’s the main line of the plot, insofar as there is one. The novel is primarily a voyage of exploration, a long paean to the wonder and variety of life in the ocean—and, prophetically, to the need to protect and preserve this life, because it’s essential to the survival of all life on earth. Aronnax and his two sidekicks are captured by the enigmatic Captain Nemo and carried along on his circumnavigation of all the seas.

Captain Nemo’s vessel is a remarkably sophisticated submarine capable of penetrating all the way to the bottom, withstanding pressures that Verne is scrupulous to explain to us, complete with mathematical calculations. It travels in secret, avoiding all contact with the land, though it’s been seen often enough, and done enough damage to shipping (either intentional or not), that the Americans mount an expedition to hunt it down and kill it. Aronnax is invited along on extremely short notice, in the belief that he’s on the track of a giant narwhal. “Hunting the unicorn,” as he puts it.

What he finds is far more than he ever expected. He’s a captive, but for the most part he has freedom of the ship, and Captain Nemo shares the wonders of his underwater world. From the uttermost depths to the ruins of Atlantis to the wonders of the Great Barrier Reef and the Sargasso Sea and an imagined, as yet undiscovered South Pole, Aronnax marvels at them all, and catalogues them in exacting detail.

Before science fiction was a thing, before worldbuilding was a word, Verne was doing it. Without computers or search engines or digital cataloguing, he did all the homework and put it all in. It’s hard science fiction in its original and most classic form. Here’s the alien world, here’s the tech that gets us there, here are the intrepid male humans who lead the expedition. In Walter’s translation, it’s as compulsively readable as the best of Golden Age SF.

Some things Verne does not get exactly right. Walter’s introduction notes particularly that Verne’s sharks hunt like crocodiles, showing their bellies and performing a death roll. He describes squid as having eight arms rather than ten, as well. But he gets so much else right that these end up being minor glitches, small indications that science of the time still had a few things to learn.

As an introduction to our section on the creatures of the sea, Verne’s novel is pretty close to perfect. It’s a grand compendium, a catalogue of wonders. It shows us everything, from the tiniest microscopic creatures known at the time, to the enormous whales and the giant devil fish, the Kraken itself, the squid so huge it can take down a full-sized ship. It doesn’t know what we know about the weird and wonderful life in the deepest seas, but it comes awfully close in places. And sometimes it comes close to poetry. Here’s a bit, one of many:

The Nautilus had drifted into the midst of some phosphorescent strata, which, in this darkness, came off as positively dazzling. This effect was caused by myriads of tiny, luminous animals whose brightness increased when they glided over the metal hull of our submersible. In the midst of these luminous sheets of water, I then glimpsed flashes of light, like those seen inside a blazing furnace from streams of molten lead or from masses of metal brought to a white heat…. For several hours the Nautilus drifted in this brilliant tide, and our wonderment grew when we saw huge marine animals cavorting in it, like the fire-dwelling salamanders of myth. In the midst of these flames that didn’t burn, I could see swift, elegant porpoises, the tireless pranksters of the seas, and sailfish three meters long, those shrewd heralds of hurricanes, whose fearsome broadswords sometimes banged against the lounge window.

Captain Nemo sums it up in terms as clear as any in later science fiction:

This is a separate world. It’s as alien to the earth as the planets accompanying our globe around the sun, and we’ll never become familiar with the work of scientists on Saturn or Jupiter.

But this we can see, he says, and explore, and try to understand. It’s the voyage of a lifetime—literally, in his case. He lives and fully intends to die in this alien world that’s still a part of our own.

That was actually the conventional scientific wisdom at the time, dating right back to Aristotle’s Historia Animalum

So I think Verne gets a pass here.

I see Verne as an object lesson for hard-SF writers like myself. His books were grounded in the best, most accurate science of his day, and a great deal of it is now known to have been wrong, if not downright ridiculous. Who knows what people in a century will think of the most accurate SF of today?

This book, From the Earth to the Moon, Journey to the Center of the Earth. Read all three in whatever translation was in the Fairfax County library in the mid to late 70’s.

May have to order this one for the TBR pile. Might get to it in a decade or so…

An abridged version of this was my very first introduction to science fiction; I must have been 8 or 9 I guess. So it has a special place in my heart (I did read an unabridged version nearly a decade later in my local library). And soon after that, the message from Arne Saknussem in Journey to the Centre of the Earth gave me a lifelong love of puzzles and word games which is still going strong nearly 4 decades later!

Also…hi Amit :) Been ages!

I read an abridged version of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea when I was that age as well, or possibly a little older. More specifically it was what I have since learned was a Moby Books Illustrated Edition, a collection of literary classics that were published as small, squarish books with an abridged version of the text on the left-hand pages, and illustrations on all of the right-hand pages (I remember reading Around the World in Eighty Days and Journey to the Center of the Earth from the same series). I am pretty sure that I read an unabridged version eventually as well.

Should have known you’d surface here, lakesidey! It’s been too long.

I tend to lurk occasionally but haven’t been engaging online much in ages :) Trying to reduce my screen time but Reactor is too tempting to completely let go of it…

“He describes squid as having eight arms rather than ten, as well.”

Strictly speaking, squid do indeed have eight arms (the thicker ones with suckers all along their length) plus two tentacles (the thin ones that flare out at the tips).

I’m somewhat stunned. I don’t think I’ve ever fully realized that Verne’s stuff wasn’t written in English. Looking at the copy of 20,000 Leagues I got when I was 7 years old and there isn’t a mention anywhere in that printing that it was translated (or abridged), so no wonder I’ve been mistaken for decades. Now I really want to check out one of these faithful translations. The book, the Disney film, and heck also the stuff Alan Moore did with the characters in his League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comics have always really captured my imagination.